At the end of Everything Is Copy, Jacob Bernstein’s insightful 2016 documentary about his mother’s life, there’s a clip of Nora Ephron discussing her final film, Julia & Julie, on Charlie Rose. She explains what the film is about — “Love” — but elaborates enthusiastically about the depiction of Julia Child’s “romantic marriage” to Paul Child. Of the relationship that plays out onscreen, Ephron says: “It’s a kind of marriage that actually exists. Thank god it does or people would accuse me of making this up! But there are guys who really do take enormous pleasure in their wives’ growth.” While her husband, Nick Pileggi, was reputedly one of those guys, her acknowledgement that these men are rare to the point of seeming fictitious exposes a dark truth about American culture, one we’re deeply invested in denying because it reflects so poorly on our national character. America is not teeming with well-adjusted men who encourage, let alone facilitate, the success of women. [Translation: If you can’t comfortably call yourself a feminist, dude, you’re a major part of the problem.]

There’s a fuse burning throughout Everything is Copy. Nora Ephron is gone but she feels alive for the duration of the film. This is not, as some reviewers opined, because of her work. Nor is it because she’s living on through her talented friends and family, although they shoulder her legacy beautifully. Ephron feels alive because she externalized her thinking process throughout her career. She performed self-reflection. It’s impossible to hear her words or watch her interviews without being drawn centripetally to the very moment she was in. We are all with Nora, processing, now, and almost always that means we’re processing a relationship, real or imagined, and parsing the exquisite differences between women and men from the point of view of an intelligent, outspoken woman. That Ephron was thorny and honest made her observations liberating; that she was an unabashed romantic made her absolutely inspiring.

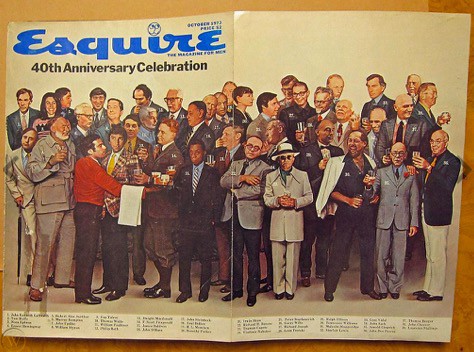

In 2020, the internet is a broken faucet streaming endless first-person tales, but in 1982 there were exponentially fewer of these, and what was in print came almost entirely from men. In that moment, Ephron’s novel Heartburn, a lightly fictionalized tragicomic chronicle of her marriage to and divorce from famed journalist Carl Bernstein, was the ideal earthquake to rattle established norms. Ephron’s irreverent tone made a mockery of the unspoken rules that dictated how women should and shouldn’t behave when cheated on. Ephron was the wronged party, but she had a formidable voice that equaled Bernstein’s, so she stepped up and took control of the narrative with bravado socially unbecoming for a woman but culturally celebrated in a man.

Ephron’s choice to lay bare the private details of her marriage and Bernstein’s cheating was a gift to women everywhere. Her refusal to quietly accept the terms of “cheated-on wife” and instead write humorously and honestly about her experiences marked a turning point in women’s perception of marriage. Ephron engineered national dialogue about infidelity and divorce, and later, after much litigious handwringing, she and Mike Nichols pressed the message home through the film adaptation of the book.

Her justified anger woke people up to the double standards women were forced to live by, and the artificially-imposed conflict women faced over whether they could get angry at being lied to, and how. In other words, Ephron facilitated the earliest “conscious uncoupling,” although a better term would be “honest divorce.”

Quite a lot of Everything is Copy is devoted to Heartburn. There are questions of morality — was it fair to Carl Bernstein to air his dirty laundry in a novel and, more importantly, was it healthy for their two children to witness a protracted public battle between their parents — both questions laid at Ephron’s feet, despite the transgression belonging entirely to Bernstein. Alongside this retelling, Nora’s sisters — Delia, Amy and Hallie — describe the troubled family life they endured growing up, their parents’ alcoholism, and their cheating father. Ephron’s younger sister Hallie astutely notes that it was cruel of their father to deny his womanizing to his wife and children because his transgressions would have explained their mother’s crazy behavior. He was gaslighting them all with lethal consequences. Their mother, Phoebe Ephron, an Oscar-nominated screenwriter, died at the age of 57 of cirrosis and an overdose of sleeping pills. On learning this, I wondered if, beneath the vindictiveness, Nora actually wrote the book not for her mother, nor for herself, but for her children.

Ephron was determined not to die of a broken heart as her mother had, but in the shadow of her mother’s example she couldn’t have known with certainty that she could pull off the impossible, even as she holed up at editor Robert Gottlieb’s home in New York and furiously wrote her fateful first novel. If grief overtook Ephron the way it overtook her mother, then at least her children would have a manuscript with answers. Even if the book never made it to print, even if it took decades for her message to reveal itself, I can’t think of a better way to explain lovesick humanity to your children than through humorous, incisive, self-deprecating fiction. While Heartburn was perceived entirely as Ephron’s revenge against her cheating husband, this one-note interpretation came from male-dominated media commentary. Heartburn was an incredible sacrifice of privacy for Ephron, too, as she opened herself up to public scrutiny. In my experience, this sort of act is really only done in fundamental pursuit of salvation.

Her choice bore out. Her book was a success. Her life restarted and she ascended to greater heights in love and career. Meanwhile, a photograph of Ephron standing with Bernstein on either side of their college-aged son testified to a positive outcome for their family, certainly more positive than the fate of her own parents. The Ephron-Bernstein divorce may have been acrimonious, and her writing seemingly vengeful, but the act of bringing her pain out into the open saved her, and served as a hopeful example to women everywhere who needed permission to save themselves.

For that reason, the moment I wanted from Carl Bernstein in Everything Is Copy was a posthumous thank you to Nora. Crazy, I know, but hear me out: I wanted him to express gratitude for her bravery during an uncertain time, with the wisdom of all that came after. Everyone in the film acknowledges how hard it was on Bernstein to be cuckolded, and you can literally see the shivers ripple through even her closest friends at the thought of standing in the spotlight of Ephron’s glare. He’s not short on sympathy. However, Bernstein’s no dummy. He knows that Ephron showed women another way to deal with the pain of betrayal, a way that claimed a happy ending as a rightful outcome for anyone who has been abandoned or deceived. He’s certainly capable of acknowledging that Nora’s survival was an immeasurably better outcome for their sons than a version of her mother’s descent into madness and alcoholism. To the extent that she saved herself, she also gave Bernstein a better future. In 2020, that message needs to come home to millions of women, and it can only be conveyed by self-assured, intelligent, feminist men. It’s time for men to finally get it. Otherwise, I’m afraid we’re looking at four more years of Donald Trump and the end of democracy as we know it.

The question Jacob Bernstein poses in the documentary is a strong one, namely did his mother ultimately agree with the mantra she inherited from her mother. Is everything copy? Ephron lived by this mantra. She built an amazing career out of it. But at the end of her life, she reversed course. She died very much as she lived, with immediacy. The second half of Everything Is Copy deals with NORA’S BETRAYAL OF US. For many of her friends, her decision to hide her grave illness is a psychic palm print that still stings the cheek. By holding everyone at bay until the very end, Ephron demanded real-time self-reflection from capable, if reticent, friends who had to process her loss without preparation or direction. Nora left without giving instructions. They had to move on without her help.

There’s so much to love about Nora Ephron that a posthumous documentary about her can be unflinchingly honest and leave the audience only loving her more. It’s a flawfest that one imagines Ephron would have loved and hated — loved for the juicy truths, and hated that they were solely about her; hated because she couldn’t edit or comment; hated, most of all, because she’s no longer here and no longer writing the story. That last part? I hate it, too. We all do.

Everything is Copy is available to stream everywhere.