Stragglers from the “ideas” file.

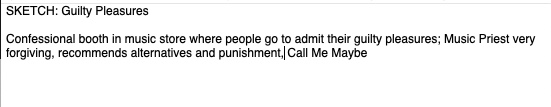

February 13, 2011 — sketch notes

October 30, 2008 — notes for Ch. 8 of first draft of novel

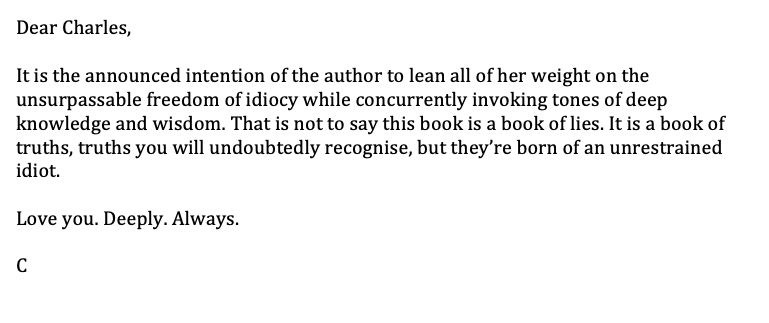

June 8, 2015 — Epistolary Satire between separated editor-husband and writer-wife as she travels for her new book; title??; Ch. 1

Ch. 2, jotting down opening prose

Theoretically, everything we learn is proof of something we already know.

Her hand reappeared from the depths of her bag covered in oily black ink. She plunged both arms into the tote and swam around until she located the promiscuous fountain pen and straying cap. Her palms, fingers, knuckles, wrists, forearms and left elbow were soiled. A cartridge of ink had stretched itself far beyond anyone’s estimation. The Schaeffer Company would be proud. She brushed a gnat from her face and caught her nose. Smudge. This wasn’t a glamourous arrival. This was karma giving her the finger.

Charlotte Dorr, the famous writer, walked with her palms up, carry-on bag hooked under her elbow, the damp, capped pen held at a safe distance from her body, and searched for a bathroom. It occurred to her that writing was little more than staining a page with thoughts. Her skin was bathed in lost ideas.

When she returned from the loo the crowded hall had emptied. The conveyor belt shuttled one pathetic little bag in dismal circles. It was not hers. She set off to Customer Service.

“Buonjourno.”

This would be her first attempt at communicating in Italian in several years. She gave up immediately.

“I seemed to have lost…” she pointed urgently with light blue hands “…Do you have the leftover luggage from Flight 306?”

A gentleman glanced up. He was seated at a low tabletop, in contrast to the high counters that shielded airline employees from the general public back at Heathrow or JFK. The English and Americans were up to their necks in work while the Italians were only up to their asses. Six employees gathered behind the desk with barely enough room to move, the women wearing neck scarves, the men in too-nice suits, studying an array of important papers that took precedence over Charlotte’s missing luggage.

The youngest of the group, a bizarrely handsome luggage agent, gathered the papers and tapped them proficiently on the desk until they fell into beautiful order. Charlotte stared at his gorgeous hands. They were manicured. They rested the papers on top of the counter and spread all ten perfectly tanned fingers across the top page.

“Si.”

She gazed at the nude, wanton hands and had the unreasonable thought that she was in love. Under the spell of jetlag every interaction was intimate and sexual or remote and surreal. For the rest of the day this warped sense of time and sex would control her. She loved his hands.

“Signora?”

“I was on Flight 306 and my luggage isn’t on the belt…” She pointed again and held out her ticket. It was illegible, bathed in ink.

***

Twenty minutes later, she was in a musty taxi speeding into Rome.

Her head rested on the cracked leather seatback. She tuned out the driver who practised the urban Italian method of passing a day by free-associating with strangers until a topic caught fire. Every conversation on every street corner in Rome was a verbal stomping to put out such fires as these. She’d foolishly convinced the driver that she was Italian with five perfectly pronounced introductory words and now he felt uneasy because she wasn’t participating in obligatory banter. It’s a terrible idea to offend an Italian taxi driver, she thought. I’m going to find myself on the street.

“Per favore…mi dispiace molto. Un longo volo.” She was sorry for her silence. It was a long flight. He sniffed loudly, sniffed again, and looked out of the side window. He was contemplating whether to leave her, she thought. The taxi appeared to drive itself in precarious bursts while the driver was distracted. He devised a truncated question for his reluctant conversation partner that she couldn’t refuse. Satisfied, he looked back at the road.

“Da dove?”

“Los Angeles, via Londra.”

His shoulders tensed and he sat up at the wheel.

“Quante ore?”

“Twenty-two.”

He tipped his ear toward the back of the taxi on hearing her English. English! He muttered to himself in lyrical bursts and Charlotte closed her eyes to soak up the verbal opera. She gathered from his soliloquy that it wasn’t the first time a foreigner had tricked him, but she guessed that each instance was a successively worse injury to his ego.

*

“Ciao.”

She said it to his face with a smile. The taxi driver swung her suitcase and dropped it too close to her toes.

“Ciao.”

He slammed the door and was gone. She missed him.

Charlotte looked at the building in front of her. It was the wrong colour. She gathered her bags close to her body, determined not to fall prey to petty thieves on this trip. She would survey the area, find her apartment and arrive there without paying a penny to the pinching gods. A young man leaned in the doorway of a gelato kiosk. He watched her without offering to help, a singularly European behaviour that made her homesick for New York. She wanted help. She wanted someone to want to help her. She wanted to be wanted here.

There’s no goddamn numbering, she thought. She loaded herself up like a pack mule and lumbered along the cobbled street without a clue which direction she was headed. Her phone had a dead battery, much like her brain. The driver had to drop her in approximately the right place, she surmised. He wouldn’t show himself to be a poor loser. Perhaps if she wandered a few paces she’d find her building. It couldn’t be far.

Unencumbered Italians moved past her like gazelles, everywhere a swish and splash of beautiful fabric and luxurious hair. Moped engines hummed unseen, European cars sped, and all she could think was that Rome sounded like an alloy of New York. Tin foil to cast iron. Light yellow stone to New York’s leaden cement. Her homesickness passed as she took in the city, walked too far and realised she hadn’t paid a bit of attention. She wanted to lie down. Where the fuck was her building?

December 16, 2011 — hitch and america

In 2004, America was at war in Iraq. The Los Angeles Times’ Festival of Books held their second panel on the war, ‘U.S. and Iraq One Year Later : Right to Get In? Wrong to Get Out?’ that would be a seminal experience in my understanding of a longish list of topics: how a panel is conducted brilliantly, how intelligent people discuss issues when they’re actually listening to each other, how to disagree with someone and still marvel at their intellect, how to be persuaded, how to persuade, and how differently a conversation goes when the participants respect each other deeply.

The discussants were Christopher Hitchens, Michael Ignatieff, Mark Danner and Bob Scheer, and the moderator was Steve Wasserman. It was a powerhouse. Their stances weren’t opposing, rather each brought a nuanced perspective to the question of war. Hitchens was fully invested in his right-wing, go-war philosophy at the time (which he would later reverse); Ignatieff held a human rights view of calling for regime change, having spent time in the mountain regions with disenfranchised (then slaughtered) Kurds; Danner stuck close to discussing specific policies in the American political arena, holding a left-supporting view; and Scheer balanced Hitchens in rhetorical vigor with his signature left, anti-war stance.

At the center, Steve Wasserman effectively ran the best conversation I’ve witnessed to date. With an acute ear for threading these four perspectives, Wasserman was the ringmaster, leading Scheer toward Hitch, back to Danner, over to Ignatieff. That the four gentlemen permitted themselves to be led at all was quite a nod to their respect for Wasserman.

The debate ran over an hour, but it might have been ten minutes. Time flew. Ideas flew faster. In England, I had a steady diet of intense political debate, and years away from living there left me detached from a key part of democracy. It was incredible to see Americans debate well. Not sure I’d seen before. (Hitchens supplied the necessary gravitas, elevated the whole thing.) I’d forgotten that the format of debate is, when effective, an internal monologue externalised, analysed and considered.

agreed with something in each perspective

showed complexity of the issue…

April 28, 2016 — Mediocrity Acceptance Speech — use when blocked

Well, this is…embarrassing. I wrote an entirely different speech. For a different award, actually.

Some of you might be familiar…In 1959, Elaine May presented Lionel Klutz with the Most Total Mediocrity award. It was before I was born, so I’d have to wait forty years to learn of the award, on youtube — which was appropriate — and it was at that moment I knew my life’s mission.

It’s a balance. How mediocre is too mediocre so as to tip over into pisspoor uselessness? Does exceptional mediocrity push one into a category of too good to be considered blah?

For years, my dream was strengthened. Every ignored phone call. Every email I sent that went unread. Every time I wrote a blog post that got nothing more than a “meh.” Every time I pitched an idea to someone with a frozen face and thought “Yes. I’ve done it again. I’m winning.”

I foolishly thought if I devoted myself…that one day Elaine May was going to walk out from behind a big curtain and reward my outstanding, undeniable mediocrity. This…takes me out of the running, I think. It’s a tragedy, really. My whole life’s work just went down the drain.

June 18, 2015 — “Five Dollars: Net Worth”; satire putting woman on paper money

The honor of gracing the five-dollar bill would go to a woman, alive or deceased, straight, gay, or transgender, married or single, of any race, and bearing proof of physical birth on American or American Territory soil. Submissions arrived from across the globe. No physical address was provided, yet the postal service did its best to put a few letters in the right hands. The vast majority of contenders were emailed to the official address — ?? — and waited in an inbox each morning to be dutifully cataloged by Sean P. Frommer in a tiny cubicle he shared with a contract worker for Veteran’s Affairs whom he had never met. Sean had the desk every weekday from 9am to noon. He enjoyed his work.

Sean’s favorite submissions included:

Eve, from the bible

The Dixie Chicks

JAWS

George Clooney’s Wife (american now?)

Sean set up an automated filter to delete further submissions for:

Katie Couric

Bruce Jenner

Michelle Obama

Martha Washington

Amelia Earhart

He set up an entirely separate filter to count the entries for:

Oprah

The tally passed two million on the second day.

Sean also kept a running list of questions that accompanied people’s submissions and forwarded them on to his boss, who deleted most of them and returned a handful to add to the future FAQs page on the Treasury Department’s website. Sean would be tasked with authoring the page once his time freed up after the initial flurry of submissions died down.

Martha Washington was the first woman to grace a denomination of American currency, in her own right and as part of the First Spouse Program. [Technically not the first woman; lady liberty “flowing hair” on dollar coin; Martha Washington on a silver dollar coin? So — “First on Paper”]

Puts careful list together with suggestions; Word comes down his boss has left; Jack Lew has been reading his emails with great interest – so, who would Sean pick?

Sean asks for time to think about this; takes a walk around the capital; describes what he sees through new eyes; chooses an “everywoman” …who is that in America?

Conversation with a woman on a bench; takes her picture; suggests it to Lew; almost fired for it; asks for one more chance; back to the drawing board, this time thinking like a man…

??

January 9th, 2015

TRANSCRIPT OF THE MAYOR OF HOLLYWOOD’S REMARKS FOLLOWING THE FUROR OVER TODAY’S ALL-MALE OSCAR NOMINATIONS

FOUR SEASONS HOTEL, BEVERLY HILLS, CA

Mayor: Thank you. [waits for applause to die down] Thank you. First, I’d like to address this year’s Oscar nominations because — oh my goodness! — there’s been a lot of nonsense printed in the press. Let me explain how this works. Here in Hollywood, we don’t reward people for their gender, we reward people for their work. And we don’t hire people for their gender, we hire the most talented, most qualified people for the job. Hollywood is wide open for lady business. I’m going to say that again because it’s important: Hollywood is wide open for lady business. It’s not Hollywood’s fault there’ve only been four Oscar-nomination-worthy female directors in a century of filmmaking. Only four women have made Oscar-worthy films in 85 years. Incredible. I don’t want to call women out, but clearly female directors aren’t working at a competitive level. If women want to be taken seriously they need to up their game. I don’t know a single guy in Hollywood who says “I won’t work with women” or “I don’t know any talented women” or “Women aren’t funny” or “Women are too difficult” or “Women make me uncomfortable” or “Women want too much” or “I never know what women want” or “Who’s going to cook dinner?” It’s a falsehood, complete hooey that the business is a boys club. We love women here and we want nothing more than to give them power if they’ll only demonstrate they can use it productively. We welcome the ladies with open arms.

As a sidebar, my daughter suggested I do a little googling on my own and sadly I confirmed what I suspected was the case: Women have been making films for as long as men have. [pause while Mayor takes out piece of paper and puts on reading glasses] Now I think where women go wrong is to limit themselves to lady topics. I kid, of course, but just looking at this list here, these are mostly films I haven’t seen and never will see. [puts list away and takes off glasses].

I’d also like to address the unimportance of women in film, and before everyone loses their minds let me explain what I mean by that: There is no reason in the world why a young girl needs to look up to a woman. She can just as easily look up to a man and, in fact…I’m going off prompter here but we have time…I think maybe that’s what’s holding women back. What’s wrong with looking up to men? What’s wrong with wanting to be Steven Spielberg? I say to young women all the time “You don’t yell. You’re too nice. I can’t trust a smiling woman and I don’t want to argue with you about money. Be more like Steven. Or Marty. Or Cameron Crowe. He’s got a soft voice but he knows how to use it.” The harsh reality is that we can’t hire women because they don’t command enough respect to direct a movie. Simple as that. It’s not our fault if little girls ask for Barbies instead of cameras. You don’t see a lot of women plumbers, or electricians, or carpet layers, do you? Maybe they don’t like to get their hands dirty. It’s not my job to speculate.

[he winks to the camera; press corps laughs]

And while I’m at it, I’d like to speak directly to Geena Davis: Of course there are female characters in film. Plenty of them. They serve a real role. They brighten up the screen at just the right time. Stop saying “statistics etc., etc., female characters have less screen time, women always talk to other women about men, and so on.” Mean Girls was all white…excuse me…women. Geena, it’s fine to throw out numbers, but what are you personally doing about them? Get back to work. No one’s going to ask you take your clothes off now. You’re out of excuses.

Okay, that’s it for my prepared remarks. I’ll take a few simple questions. [pointing] Yes.

Female Reporter: You mentioned four exceptional female directors as potential role models for young women. Who are they?

M: Exceptional? Did I say that?

[laughter] Uh, [refers to notes]: Sophia Coppola, Kathryn Bigelow, Jane Campion and Carol Reed. I’d add Leni Reifenstahl but she was never nominated.

Female reporter: Carol Reed is…

M: And there’s our very own Angelina Jolie! How could I forget her? She’s directing now and we home grew her. She’s homegrown, so don’t tell me we aren’t doing anything about gender. We are doing something and it is working, but we can’t nominate her for anything because it will look like nepotism, and it will be nepotism. So today didn’t work for her, and it didn’t work for women, or for these remarks, but we’re all doing something important and Hollywood should be congratulated. Next? [pointing] Yes.

Male reporter: You referenced Hollywood’s role as the leader in cultural creation. Can you elaborate on that?

M: Sure. As I told J.J. the other day, guys just get it. Women enjoy it, some of them, but guys really get it. That’s why we think of guys first when we come up with storylines. The guys need that special extra something to get them into the theater, and the women always follow.

Female reporter (checking notes): You’re referring to J.J. Abrams.

M: He’s a director. One of our most important directors.

Female reporter: I know who he is, I was just…

M (pointing): Yes?

Male reporter: Transformers!

[applause]

M: Man after my own heart.

Male reporter: When is the next installment.

M: Well, I haven’t talked to Brad but we’re…there’s something special in the works. I wasn’t going to announce this today but since you’re stuck covering this other stuff I’ll give you the scoop…Hollywood is going to Shanghai.

[loud cheers, applause]

M: And we’ve signed on to build the world’s largest full-service studio in the heart of Beijing. We found the silver lining to the Chinese smog problem — no more day-for-night shoots. Costs slashed to almost nothing. Endless labor supply. I told President Xi this morning, “Je suis China.”

[applause]

Thank you.

August 25th, 2015 — 20 Questions You Must Answer Before You Get Married

When you order takeout, which one of you lamely suggests it would be cheaper to go pick it up?

If it’s you, you’re probably okay. If it’s him, no. Run. Faster. You’re not running fast enough.

Do you shop at Barneys?

You’re not doing this for the right reasons.

How often do you like to eat out every week?

If your number isn’t exactly the same as your beloved, it’s okay. If your number is different by a factor of 2 meals and one snack, consider that your lives are on different paths…going in opposite directions…and that you might be happier with someone else.

Astrology Intermission: Are you compatible?

Scorpio, with no one. Leo, with anyone. Virgo, PITA. Everyone else, you’ll be fine, but you’re definitely not with the person you think you’re with. We’re all full of shit, but 75% of the world is too self-absorbed to realise it. Duh. The Stars. PAY ATTENTION.

Can you agree to store your DVDs and CDs that you must own a physical copy of in one 3-ring binder with addable pages, or does one of you feel strongly about disc packaging and cover art?

This question is its own questionnaire. The answer can predict not only whether you should be getting married but, further, how long your marriage will last depending on who feels what about what. (Him: pro-package, 1 year; You: pro package: 5 years.)

Do you like your thighs?

Not you. Him. He answers this one. About his thighs. Listen closely. It’s interesting stuff.

Do you need to drink a bottle of wine before you have sex?

It’s okay if you do, but you should ask yourself: can I afford all of this wine? Marriage is forever.

Do you have food poisoning all the time?

Marry a doctor only. No one else is capable of ignoring you.

Can both of you fake orgasms?

If you’re tempted to answer this question in any way, do not get married.

Bath or shower?

Trick question.

Tom Cruise or George Clooney?

No matter your gender identification, this question is a shortcut to determining true compatibility. (Obviously, you don’t want to choose the same guy.)

Swingers: Lifestyle or Movie?

The answer you both say out loud is: Movie. It’s okay to change your answer after you’ve been married for a few years. Nobody’s holding you to anything. But today, right now…

Do you have any food allergies?

The answer to this question doesn’t make or break a marriage. It’s just a vulnerability you must consider every time you fight with your spouse.

Did you overshoot your engagement?

The reason these 20 Question questionnaires are 100% accurate is their speed. You know in minutes whether you’re right for each other. If you’ve already spent months or years pondering marriage while people pressure you to plan a religious ritual full of life-altering vows, you’ve missed the boat. Take the next one.

September 17, 2013 – Fighting the Bad Fight cuts

At whatever age we leave school, we quickly discover that the classroom of life is unmanageably large once we’re wholly responsible for uncovering good information, infallible sources and, most importantly, trustworthy messengers. I’ve always taken this task seriously and become cranky (see opening satirical nonsense) when highly intelligent people of all walks of life lose sight of the following:

— the endgame

— the intermediate goals

— the tools needed to accomplish those goals

— that no one can carry a movement alone

— that knowledge dissemination is an art, not a job

— that building is constructive and aggression is destructive

— that intelligence exists in hidden layers and forms

— and that potential (potential advancement, potential awareness, potential enlightenment) must be nurtured or it dies

Killing potential is near the top of my list of crazy-making experiences. A missed opportunity for learning is the express train that blows through my station. I’m left with what I already know and a frustrating blur of what I don’t.