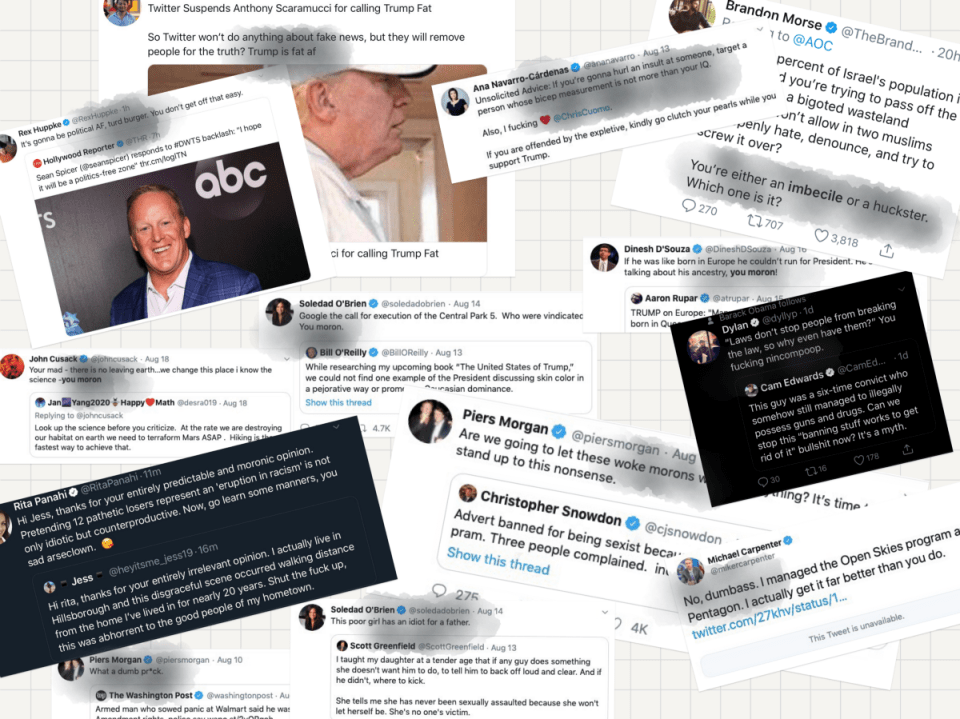

A looming future of transhumanism and the encroaching threat of climate change enshroud our daily lives. Sure, we’re facing a pandemic, a gun crisis, a healthcare crisis, unprecedented economic inequality, a crumbling democracy, impending regional wars, loss of privacy, disinformation, and a privatized space race with questionable aims, but all of that pales next to the strangeness of confronting an existential crisis of unsustainable life on earth alongside the rapid devolution of our humanity at the hands of software and machines. What I mean to say is this is a historically bad time to make the case that Hollywood should be focused on reviving the romantic comedy genre. We’ve clearly got bigger problems.

However, it’s my view that we, the imperiled public, desperately need to be watching interesting, funny relationship movies. In theaters. On dates. The communal experience of laughing in a theater while watching ourselves—regular people, not superheros—reflected in stories on a big screen is essential. It suggests we’re able to laugh at ourselves with each other, that we’re not too proud to laugh at ourselves in front of strangers, and reminds us that we share our life experiences with a large, diverse group of people. The theater is where we experience common ground. If Hollywood doesn’t find the will to make those movies, and fast, and if we don’t find the will to force ourselves to go see them, no matter how in love we are with our couches, we will most certainly never again have the necessary social glue needed to solve much bigger, more urgent problems that are presently breathing down our collective neck. (We do have a collective neck, whether we like it or not, snowflakes be damned.)

The world didn’t arrive at hell’s oasis overnight. The blueprint for our demise has been around for some time. Love and dating in America have taken a backseat to more urgent problems for years, if not in practice then at least in conversation. Hollywood turned all of its attention to comic book world-saving and space operas years ago, first because they were so lucrative, and later because they were so reliable. There’s not much happening these days on a high budget studio level that echoes WHEN HARRY MET SALLY in broad appeal, which implies we don’t care about the one-on-one love stories that used to preoccupy many of us morning, noon and night, that we’ve dropped the topic that serves as the foundation for building a life, joining social groups, starting families and forming communities. Hollywood’s output suggests that we, the viewing public, don’t find ourselves interesting or entertaining enough to warrant a big budget film. I think that implication is false (and dangerous). I think we care a lot about understanding each other, across political, social and gender divides. During the course of technological advancement, those stories have been devalued, and that’s the reason for this piece.

In 1990, the brilliant playwright and filmmaker John Patrick Shanley made JOE VERSUS THE VOLCANO. Joe (Tom Hanks) begins with tired eyes and a bad haircut, trudging through urban muck to reach his depressing basement job, and ends looking debonair in a white tuxedo, with a great haircut, newly married in the South Pacific. His wife is Patricia (Meg Ryan), whom he has known for four days. They’re married for all of two minutes before they join hands and jump into an erupting volcano. Joe does this because he wants to be a man of his word. He agreed to jump into the volcano after being told he has a “brain cloud” and only a few months to live. In exchange for the adventure of reaching the South Pacific by boat, he will end his life spectacularly. He later learns he was duped into going on this nonsensical journey and is actually in perfect health.

Patricia’s reason for jumping into the volcano is a bit murky. She spends two days getting to know Joe on her boat, the Tweedle Dee, before a typhoon sinks it, taking her entire crew with it. Joe saves her life and they survive two more days floating on his luggage—she, unconscious, he, delusional—before arriving at the island, at which point she announces she’s in love with him. She tries to talk Joe out of jumping but he’s set on a heroic death, so she asks him to marry her, they marry, and then she says she’s jumping with him. Maybe the thrill of getting married made her feel spontaneous and lucky. It’s hard to tell. They jump holding hands, the volcano ejects them in a cloud of gas and they survive. Love conquers all.

Exactly thirty years later in the California desert, Nyles (Andy Samberg) begins PALM SPRINGS looking good, if bored, and ends the movie still looking good but now nervous and awake as he takes the hand of his new love, Sarah (Cristin Milioti). They walk into a cave with a boiling time tunnel where they kiss passionately before she blows them both up with a body belt of C4. It’s very romantic.

They do this because they’re trapped in a time loop, living the same miserable day over and over at Sarah’s sister’s wedding, à la GROUNDHOG DAY. Sarah slept with the groom the night before the wedding and wakes up every morning to the awful realization of what she has done. Nyles is in a relationship with a self-absorbed younger woman and is reliving a daily hell of settling for mediocrity. By the time Sarah figures out a theoretical way to exit the time loop, Nyles has figured out he needs to be with her. He’s ready to grow up and blow himself up for love.

The message of both films is horrible when taken literally. A leap of faith, better described as “a hopeful dual suicide,” is presented as the only way forward for these endearing characters, as the only honorable choice. Metaphorically, however, the notion of taking a leap with another person, ending life as you know it by annihilating yourse…whoops, no, that’s also horrible. Both films push a fantasy narrative of complete abasement to the mysteries of the universe, on par with taking life advice from a horoscope. At no point does the audience believe the film is really going to kill these people off. They’ve come so far! They’ve learned so much! Apparently for their proverbial sins, they still have to die. At least, they think they do.

The films are both surreal fantasies with comparable endings, and they share one similarity in having unusually normal female protagonists. Neither Patricia nor Sarah are flighty, conflicted, dependent, or particularly interested in love and marriage. They’re both self-reflective, insightful and very smart, which comes across with refreshing clarity in the midst of a surreal narrative. When female characters are effortlessly normal, flawed without silently broadcasting “I’M UNLIKEABLE, DAMNIT,” the writing has delivered a rare wonder and should be congratulated.

Other than those broad similarities, the two films are notable for their differences. Baby boomer Joe is a cog in a dark, dirty corporate wheel at a medical hardware company. His life is meaningless, and it’s making him sick. The satirical commentary on what passed for a “job” in the late 80s is played to the hilt, complete with an “artificial testicals” prototype on his boss’s desk. Joe’s problem is not Joe. It’s the world he’s living in, the expectations placed on him, and society’s numb acceptance of it all without resistance.

By comparison, millennial Nyles never mentions his job. When Sarah asks what he did for a living before he got stuck in the time loop he’s unable to remember. He never asks about her job or career, although it’s later suggested that he already knows a lot more about her than he initially confesses. He’s not incurious, he’s wise. Regardless, they don’t discuss the central focus of modern life, one’s work, suggesting that careers don’t define millennials the way they define older generations. In GROUNDHOG DAY, Phil Connors uses his eternal time loop to do the things he missed doing by having a demanding job and a bad attitude, namely reading the classics, learning to play the piano, and doing good deeds. Two generations later, Sarah and Nyles face the same meaninglessness and choose to drink all day and amuse themselves by breaking every law and rule. They have no apparent interests and there’s no possible way to create anything lasting or meaningful…until they fall in love.

On the subject of sex, both films are sweetly chaste. Sarah and Nyles agree not to sleep together, given that they’re stuck in a loop and don’t want things to be eternally awkward. Eventually they relent, which serves as the catalyst to try to escape the loop and have a real future. Joe and Patricia get married before they even make out, which is a loud wink coming from the “free love” generation who danced naked at Woodstock and marched on Washington for birth control. Baby boomers single-handedly liberated sex from puritanism. By the 80s, however, boomers were divorcing in unprecedented numbers. The generation that decided it was free to sleep with whomever it pleased discovered that finding one person to go the distance with was more romantic than passion itself. If boomers had learned anything by midlife, it was that passion didn’t make a marriage. People did.

It’s unsurprising that Baby Boomers and Millennials are responsible for tales depicting coupledom as the death of the individual, a traumatic decision that one only survives by chance or miracle in explosive, spectacular fashion. Both generations take themselves too seriously. Generation X, however, is the goldilocks audience for these fables, fairly committed to the idea that it’s not good to blow yourself up and/or jump into a volcano for love, but blasé enough to use dating websites where miracles are purported to happen. Gen X was also the receptive audience to the TV fantasy of Friends, happily patterning the future on the impossible economics of a massive two-bedroom apartment in Manhattan and as much spare time in adulthood as one had in college to banter wittily with, well, friends. Gen X has a shrug-and-see attitude which makes it the ideal generational voice to reestablish a few key narratives if given the opportunity and support.

Generation X came of age during the 30 years between JOE VERSUS THE VOLCANO and PALM SPRINGS. During that time, Hollywood evolved away from the traditional studio system and moved towards corporate ownership, primarily by technology and communications conglomerates. The 2000s ushered in an era of marketing-as-tastemaking, with studio executives increasingly taking their scripts to the marketing departments before greenlighting them, often during the development process. This was new in the filmmaking process. Repeat: This was new. Film buffs can disagree all day long about how the industry has changed over the years and whether certain changes have been good or bad for filmmaking on balance, but it’s incontrovertible that this shift in decision-making gave tastemaking power to the sales and marketing side of production. In journalism, this would be the equivalent of the ad sales department for a newspaper weighing in on whether a journalist should cover a story. These two branches of media companies, business and news, are strictly separate and do not interact with each other because of the conflict of interest. (For example, the Washington Post needs to be able to cover any and all newsworthy stories, whether a tech company buys advertising space in their pages or not. A news organization should never opt out of covering a story because their advertisers are lobbying them.)

However, Hollywood is not journalism. The industry famously views itself as living by its own rules, of which there are none. The foundation of Hollywood decision-making was most eloquently summed up in three words by the late, great William Goldman: “Nobody knows anything.” Nobody is in charge. Nobody codified essential aspects of the creative process. Nobody thought to protect Hollywood’s most precious commodity from encroaching corporations. Instead, the industry frittered away its tastemaking power by demoting high quality films to “indie” status, meaning they’re made using independent financing, and instead poured all of its money into “tentpole” franchises. This began in earnest in the 90s, so by the time the Internet Age arrived with streaming technology, the studios rolled over, seemingly grateful to have someone new to blame for their imploding “business model.”

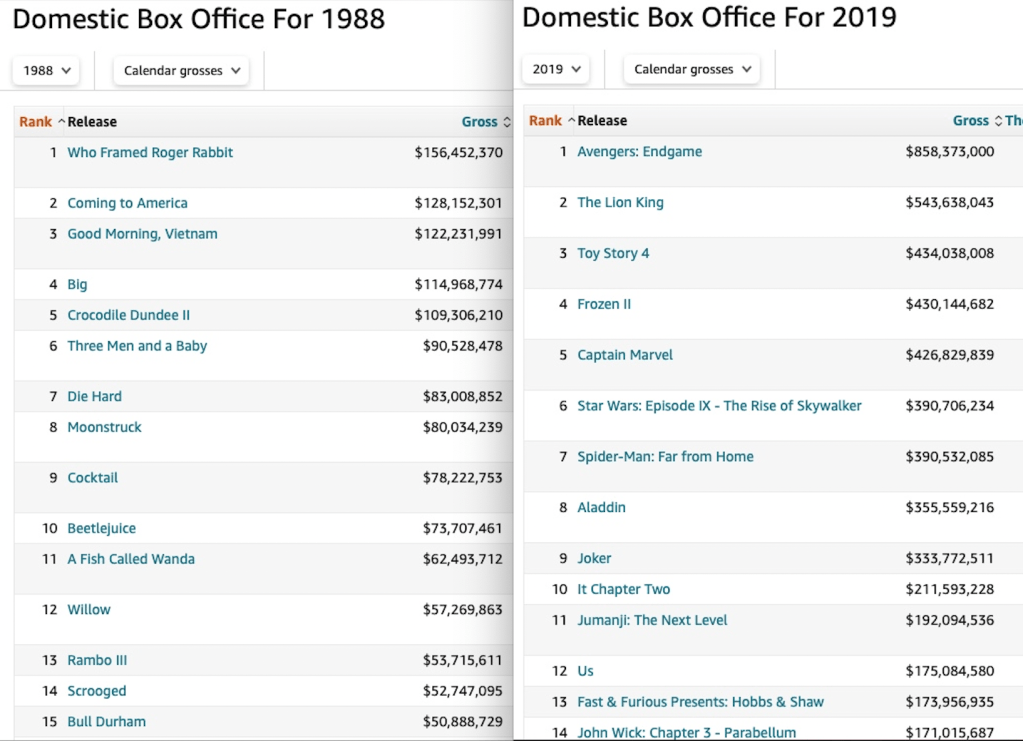

What does this have to do with romantic comedies? While Hollywood’s output became increasingly marketing-based and franchise-heavy, adult relationships became the purview of HBO and premium cable, with Sex and the City dominating the high-quality but definitively at-home viewership of relationship storytelling. A major split occurred. Prestige filmmaking no longer included relationship movies, conveying the unspoken message that adult relationships weren’t considered valuable enough for studios to support in kind alongside Batman, Marvel, Star Wars, Avatar, Star Trek, “Tom Cruise,” etc. To wit, Warner Bros. made JOE VERSUS THE VOLCANO with a budget of $25 million and it opened to $9.2 million in 1990, while PALM SPRINGS was made independently for $5 million and opened to $164,000. Granted, it opened during the pandemic, but given its budget it was unlikely to see a big opening weekend in 2020, no matter the circumstances of its release.

One interesting aside to this discussion is what Generation X filmmakers did between 1990 and 2020 with dwindling studio support. STRANGER THAN FICTION was pretty much the only mid-level fantasy-relationship studio film made during that time–made for $30 million by Sony Pictures, starring Emma Thompson and Will Ferrell. The Gen X approach to love was (I note with pride) the reverse of boomers and millennials, with Will Ferrell’s Harold Crick begging not to die because he finally found love. He’ll do anything not to die at the hands of a homicidal fiction writer who created him in order to kill him. It opened to $13 million.

While studios shifted their focus entirely to CGI-heavy franchises, theaters moved to upgrade the theatrical experience to accommodate them, touting high-tech sound systems, screens and 3D capability, all of which sent the cost of movie tickets through the roof. Today, filmgoers rightly balk at paying the same price to see a Star Wars film a Sex and the City movie. Only one of those films requires expensive bells and whistles to get its story across.

Between the loss of support in script development to the theatrical focus on animation and sci-fi with CGI, the film industry essentially dropped an entire genre on its ass without considering the long-term effects on the culture it was entrusted with influencing. Presently, there is more discussion in the trades about whether China is carrying the latest tentpole offering from Hollywood than the overall quality and content of output in American theaters in general. American audiences aren’t Hollywood’s primary concern anymore, and that is most obvious in the snapshots of box office earnings year over year. With the business geared towards foreign audiences, it should be no surprise that movies about interpersonal relationships have dropped in status, since the nuances of relationships, humor and love are highly specific to each culture, hence those films don’t translate easily overseas.

Thus, younger generations of Americans are getting their top-tier entertainment-based insights on adult relationships from broadly drawn superheroes sprinting toward each other, futuristic guns drawn, ready to fight for a magical orb that will save the universe, not wittily navigating the treacherous end-of-dinner decision about who picks up the check on a first date. This may sound like an inconsequential overgeneralization, but the shift in Hollywood’s tone and storytelling has real-world effects for kids growing up in a franchise-dominated, entertainment-heavy culture. There’s no angst-ridden wait of several years between buying a ticket to a G-rated Disney animated film and an R-rated live-action one, of staring up at the marquee with longing and thinking about being able to see any number of movies without sitting next to a parent. Today there are mere inches on a screen between clicks, and the short jump from animation to sci-fi has very few relationship films vying for attention in between.

This 30-year reliance on sci-fi fantasy franchises and the implied value of those stories over relationship fantasies is, in my view, responsible for quite a lot that isn’t good in the 2020s. When an entire industry devotes the lion’s share of its resources to superheroes and the distant future, it neglects the dreams and fantasies of real people who are buying movie tickets. Nobody sitting in the theater relates to a superhero the same way they relate to an average guy who hates his job, who has no life, or who needs an adventure. Nobody sitting in the theater relates to someone who flies around on a spaceship the way they relate to getting nervous about getting married, or pondering their future, or questioning what their purpose is. When people stop viewing their own lives as interesting, and their own problems as being worthy of having movies made about them in a fun, fantastical way, they’re encouraged to devalue regular life. There are many reasons why people walk around staring at their cellphones these days, their attention freely given to a tiny screen while life happens in real time around them. This is certainly one of them.

The process of elevating a future that doesn’t exist yet over a present that needs attention is a major contributing factor in our social dysfunction. The evidence is in the films themselves. JOE VERSUS THE VOLCANO is one man’s escape from the drugery of his life. He seeks help from doctors, begging for a reason why he feels so sick inside. He jumps into a volcano under false pretenses, despite being newly married to a woman he loves, because finding meaning in life is even more important. Had he known the truth about his health, he would have refused to jump and continued to search for hope and answers. Thirty years later, PALM SPRINGS is a story of two people trapped in meaningless time. They only recognize each other and fall in love because time has been reduced to one day. If not for that, they would pass by each other and continue on with their empty, dissatisfying lives, distracted by what they’re told is meaningful, unaware that there’s something better right in front of them if only they could slow down and see it.

Hollywood used to be our time loop, slowing life down for a couple of hours with sharp, compelling relationship movies that encouraged us not to take ourselves too seriously. If there’s any risk to be taken in the business now, the essential one is to push for a return to more traditional filmmaking, and to search for the writers and directors with a fresh perspective on love and relationships, and new stories to tell. In my view, studio support for this genre would make a substantive difference in the direction the world is taking, while entertaining people in the process.

If you read this, you owe me a dollar.

I don’t work for free. Donate $1 to www.wikipedia.org, or somewhere that matters to you.