America’s Addiction to Black and White Thinking

Errol Morris (off camera): If the purpose of the war is to get rid of Saddam Hussein, why can’t they just assassinate him? Why did you have to invade his country?

Donald Rumsfeld: Who is “they”?

Morris: Us!

Rumsfeld: You said “they”! You didn’t say “we.”

Morris: Well, we. I will rephrase it. Why do we have to do that.

Rumsfeld: We don’t assassinate leaders of other countries.

Morris: Well, Dora Farms we’re doing our best.

Rumsfeld: That was an active war.

(Transcription)

Young children think in black-and-white terms. Something is good or it’s bad, the answer to all questions is a variation of “yes” or “no,” and anything more complicated results in frustration. Once kids master basic reality then they move on to complexity. Someone who does a bad thing, like kick you in the shin, isn’t necessarily a bad person, and someone who does a good thing, like offer you candy, can’t automatically be trusted. Grasping that life is nuanced is a rite of passage that signals maturity and readiness for greater responsibility.

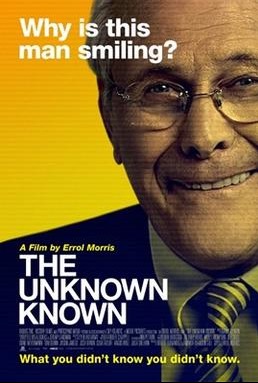

If media and culture are taken as a fuzzy reflection of American tastes, it’s evident that the country needs its leaders to be heroes or bad guys. The public seems largely indifferent to anyone who doesn’t enthrall or disgust it. People demand “the truth” when it’s staring them in the face, they just can’t see it for all of those pesky conflicting details. Such is the case with Errol Morris’s fascinating documentary, The Unknown Known.

The film’s subject is Donald Rumsfeld, the charismatic politician with an uncanny knack for finding a seat in the Oval Office during nearly every political crisis since the 1970s. A Princeton graduate and Navy pilot, he was elected to Congress in 1962 at age 30 and went on to hold several posts in the Nixon administration (during which time he hired Dick Cheney as his assistant.) In 1973, he became the U.S. Ambassador to NATO, a fortuitous departure from Washington that allowed him to emerge unscathed from Nixon’s disgraceful exit and return to the White House as Gerald Ford’s Chief of Staff. He subsequently became the youngest Secretary of Defense in history, then moved into the private sector as CEO, and later Chairman, of pharmaceutical company G.D. Searle. George Shultz asked him to return to public service following the Beirut Barracks attack that killed hundreds of American soldiers in 1983, and Rumsfeld set off on a fact-finding mission as Ronald Reagan’s Special Envoy to the Middle East. He was also notably a lead contender for Reagan’s Vice Presidential running mate, although the position ultimately went to future president George H.W. Bush. Most people know Rumsfeld best for his final tour in Washington as George W. Bush’s Secretary of Defense from 2000–2006, the guy who took America into prolonged, unsuccessful wars in Afghanistan and Iraq in the years following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. In 2014, Rumsfeld is home. Our troops are not.

The Unknown Known doesn’t present any groundbreaking information on history or the six decades Rumsfeld has been in and out of public office. Instead, it recounts what we already know and, in the process, presents an inconvenient truth about American culture: Americans habitually disavow the known knowns of power and democracy when they dislike an outcome. When a country is debating whether a war or a leader was good or bad, honest or evil, it’s safe to say no substantive lessons will be learned.

In his New York Times supplementary pieces, Morris says that The Unknown Known was his quest to pin Donald Rumsfeld down and get some answers to the quagmire of the Iraq war (never mind that Rumsfeld famously stated he “doesn’t do” quagmires.) The entire press corps and media establishment could not accomplish Morris’s goal during Rumsfeld’s ill-fated second stint as Secretary of Defense but this is insufficient evidence for Morris that his objective is a fool’s errand.

For reasons that aren’t disclosed in the film, Morris is a biased, bordering on hostile, interviewer. Perhaps he felt obliged to play the role of interrogator due to the mistreatment of detainees on Rumsfeld’s watch, or maybe he grew frustrated as his questions sent him in familiar circles. No matter the reason, the film is both riveting and disturbing as it illustrates our cultural addiction to black and white thinking, even when we’re prepared and committed to dig for answers.

While American soldiers are still hard at work over in Afghanistan, Iraq, and now the entire Levant, Morris frames Rumsfeld’s account of sending troops to the Middle East as utterly lacking intelligence or rationality. For some, any war lacks intelligence and rationality. Morris’s line of questioning seems to place him in that category. His interview with Rumsfeld plays out as two opposing ideologues who have no interest in understanding each other, only in being understood. An award-winning documentarian with a sterling reputation, Morris indirectly reveals the crux of our national dilemma: We already know everything we need to know here. The real question is: What are we prepared to do about it?

To make the best possible decision, it’s worth laying the cards on the table and playing an open hand.

Known #1: Rumsfeld Left a Prolific Paper Trail

It’s apparent during the film that Rumsfeld is a guy who strictly adhered to the rules and expected others to do the same. He was “dumped” by Nixon in 1973 for not being crooked enough. He was willing to stake his job on corralling Condaleeza Rice when he perceived her to be overstepping her bounds as National Security Advisor. Most notably, he left a paper trail of memos he estimates to be in the “millions” that communicated his thoughts throughout his years of public service. This isn’t a guy who seems to have anything to hide, yet that’s evidence no one wants to acknowledge because it runs counter to the bad guy theme.

Morris raises the topic of Richard Nixon’s proclivity for self-recording. Rumsfeld offers the explanation that perhaps the wayward president felt everything he said was valuable. Morris asks if Rumsfeld knows of any president since who made similar recordings. Rumsfeld says he does not and suggests that people tend not to make the same errors as their predecessors but instead make “original” mistakes. This thinking highlights the key to Rumsfeld’s confidence and serves to make him a compelling figure. While Morris tries to draw a comparison between Rumsfeld’s millions of memos to Nixon’s omnipresent tape recorder, it’s the differences that are most striking. Rumsfeld’s memos were overt and, by his own description, his primary tool of communication with his staff. They were “working documents.” For sheer bulk and publicity, Rumsfeld’s “snowflakes” seem like a precursor to the cult of selfies more than an echo of Nixon’s paranoia. Further, being working documents, the snowflakes were intended to be fluid, even ephemeral. No matter how we choose to interpret the facts, Rumsfeld offers plenty of evidence that he’s working above ground which contrasts sharply with the vacuum of available memos authored by Dick Cheney, Karl Rove, and others in the G. W. Bush Administration.

Morris observes that Shakespeare portrayed historical conflicts as entirely hinging on infighting and personality struggles between individuals in power. This comment follows Rumsfeld’s refutation of any meaningful strife between himself and George H.W. Bush in the years leading up to a presidential candidate fork in the road. It’s interesting that Morris opts to leverage a playwright who dramatized monarchies for the pleasure of a monarch against Rumsfeld’s feathery dismissal of personality politics in American democracy. The blueprints for America’s polarization are on display here: The imagination of those not in power (Morris, Shakespeare) leans toward notions of infinite unchecked aggression, while an erstwhile decision-maker in the most powerful government in the world (Rumsfeld) privileges the process and the system, and grasps the limitations of what one man can actually do with his aspirations in a democracy. Nixon abused his power, was caught and ejected. Rumsfeld recorded his thoughts and intentions publicly and stands by those thoughts today. Morris goes after Rumsfeld as though Rumsfeld is hiding in plain sight, but his questions assume that Rumsfeld has something to hide in the first place. Is it possible the only thing Rumsfeld concealed was his ambition? And if so, based on his track record, did he even conceal it?

How could a man who is so transparent have duped the public into war? In a dictatorship, people are cowed into submission and given no choices, but in a democracy it isn’t rational to claim that an entire population was mystified. A handful of representatives cannot lead a vast, multifaceted, democratically empowered people so far afield of their purported values. Asserting otherwise is an abdication of responsibility, and getting to the truth of what America wrought in the aftermath of 9/11 will require accountability on all sides of the equation. Democracy is predicated on power residing in the people.

Known #2 – Saddam Hussein did not have Weapons of Mass Destruction

A telling exchange unfolds when Rumsfeld discusses the hunting and eventual capture of Saddam Hussein. His subordinates asked him if he wanted to talk to Hussein. Rumsfeld declined. In the film, Rumsfeld says the person he would have liked to talk to after all was said and done was Tariq Aziz. Aziz was Hussein’s Deputy Prime Minister and right hand man who Rumsfeld first met on his travels through the Middle East in the 1980s. The two men spent hours in conversation and Rumsfeld found Aziz to be a rational guy. He says he would’ve wanted Aziz to explain what alternative approach might have worked to get the Iraqis to “behave rationally.”

With all of the additional evidence we now have about the Iraq War, it’s odd that Morris doesn’t take this opportunity to reframe Rumsfeld’s perspective here. Granted, Morris would have to sympathize with our enemy, a dictator, to point out that the United States was the irrational actor. Saddam Hussein perpetrated unforgivable violence on his own people, but his misreading of his situation vis-à-vis America in 2003 is entirely understandable. America did to Iraq what it should have done to Pakistan if it was serious about invading countries that harbored terrorists connected to 9/11. Hussein couldn’t possibly anticipate the actions of an irrational superpower. America stepped onto the world stage and presented false/made-up/incorrect “evidence” of a nuclear bombmaking program Hussein did not have as justification for starting an illegitimate war.

In playground vernacular that Rumsfeld might appreciate, America got kicked, so it turned around and kicked someone weaker, harder.

Why Morris doesn’t put this to Rumsfeld speaks to how far back we need to go to sort out the context for our decisions, and how deep we need to wade into the dark questions of what we’ve done. The risk is that we’ll be forced to absolve a few bad actors of wrongdoings, that we’ll show characters like Hussein to be less evil or crazy than we need them to be to feel okay with ourselves. Should America forgive itself for acting irrationally after 9/11 and pursuing revenge in lieu of justice? Eventually, but that forgiveness can only come with acknowledgment of its mistakes. That Morris doesn’t take Rumsfeld to that place, a place so many of us want to go, is a missed opportunity to find consensus between polarized Americans. Morris won’t let Rumsfeld off the hook and Rumsfeld won’t ask to be released. It’s gridlock that is breaking the country.

Known #3 – Rumsfeld Was Not the Chief Architect of the Iraq War

Morris: When you’re in a position like Secretary of Defense, do you feel you are actually in control of history, or that history is controlling you?

Rumsfeld: Neither. Obviously you don’t control history, and you are failing if history controls you.

This is an excellent answer. It is representative of almost all of Rumsfeld’s answers to Morris’s questions. Morris gives Rumsfeld two options: Are you a megalomaniac or a pawn? Do you believe you control the world, or that you cannot be controlled? Rumsfeld responds by exposing the black-or-white supposition buried in Morris’s question but doesn’t go further by revealing a third option as he sees it. Both of these guys are smart enough to come up with a third option, even one they might agree on, but neither sticks their neck out to hazard one. They’re both too vexed by a need to be understood. (Answerer: Here’s why I did this. Questioner: Here’s why I hate it.)

The question remains why Rumsfeld didn’t guide the country toward a bit of soul-searching in advance of going to war. If history isn’t going to have us by the tail, if we’re not going to “fail” by Rumsfeld’s definition, we needed to pause and collectively ensure that our actions were informed by history, but also by values, ethics, and newly formed goals in a scary new landscape. With so much knowledge of political decision-making under his belt, Rumsfeld would have been an ideal person to help us ask: Will we feel better about 9/11 after one, two, three…or thirteen years of war? Will we feel avenged by the death of more Americans, and foreign innocents? With the years now passed and the death toll so high, the answer is definitively no. We will not.

As I watched Rumsfeld lay bare his methods of decision-making and politicking, I thought of the complexity of holding high office. Bush and Cheney knew what they were doing when they brought “Rummy” into the White House in 2000. In hindsight, the obvious reason to choose Rumsfeld out of a pool of highly qualified candidates was his willingness to serve the country’s leadership, to voice his opinions in his area of expertise, when requested, and then make decisions and follow directives without looking beyond the well-defined boundaries of his domain. He was not in charge of intelligence gathering, as he points out. Intelligence combined with Rumsfeld’s suggested policy of “ridding the world of terrorism by going after states that harbor terrorists” formed the case for invading Iraq. Yet, Rumsfeld admits to Morris that he heard of the decision to go to war with Iraq from the Vice President in front of the Saudi ambassador. Rumsfeld wasn’t exactly in the driver’s seat.

In 1983, Rumsfeld toured the Middle East as Special Envoy and sent “cables” back to Washington, including the now-famous “Swamp” memo to Secretary of State George Shultz. Morris asked Rumsfeld to read it aloud for the camera. In the film, Rumsfeld’s words are heard over images, presented as one continuous paragraph. In fact, it is a series of excerpts. On my first viewing I mistakenly thought this was a reading of the entire memo, but when I searched for the document I found it was much longer and more involved than its presentation. The following is transcription from the film. I’ve added ellipses to show where the memo breaks:

Rumsfeld (voiceover): I suspect we ought to lighten our hand in the Middle East. … We should move the framework away from the current situation where everyone is telling us everything is our fault and is angry with us to a basis where they are seeking our help. In the future we should never use U.S. troops as a peacekeeping force. … We’re too big a target. Let the Fijians or New Zealanders do that. And keep reminding ourselves that it is easier to get into something than it is to get out of it. … I promise you will never hear out of my mouth the phrase “The U.S. seeks a just and lasting peace in the Middle East.” There is little that is just and the only things I’ve seen that are lasting are conflict, blackmail and killing.

Oddly, Morris omits the final two words of the memo after killing. On the page, Rumsfeld finishes “ — not peace.” Peace is on Rumsfeld’s mind, or it is at least part of the government’s agenda. He does not see it as viable in the Middle East and the memo lays out his sense that America shouldn’t participate there without an invitation, and only in a limited capacity. The entire 8-page memo provides incredible insight into the region at that time and the key players.

Given his strongly worded assessment, it seems unlikely Rumsfeld would have waged a full-blown war there, even 20 years later, if left to his own devices in the aftermath of 9/11. Military action would undoubtedly have been part of any president’s response – Special Forces operations to find Bin Laden would have been on every agenda post-9/11 – but there’s no line drawn, A to B, that indicates a full-scale invasion of two Middle Eastern countries would have been at the top of Rumsfeld’s list of priorities. I was left with the leaden feeling that if Rumsfeld had been Reagan’s chosen running mate three decades ago, rather than G.H.W. Bush, that the country mightn’t have gone to Iraq in the first place with President Rumsfeld at the helm. While Americans may not like the ambiguity, it’s worth remembering that it’s possible to be a warmonger without waging an actual war.

Known #4: American Values Have Shifted

This final card is either the Joker or the ace in our deck. Values are abstract and thus difficult to define, but the discussion is crucially important because it illuminates the context for our decisions. A ramping up of self-centric thinking over the last several decades has lead to a pronounced shift in our concept of civic duty. Personal power captures our imaginations more routinely than national achievement. Steve Jobs is a god, Warren Buffet is a guru, and Beyoncé is America’s “Queen Bey.” America openly worships successful individuals, which is surprising behavior from a country whose defining political victory was independence from a monarchy. Yet in 2014, the public seems eager to bow to a handful of individuals without considering the toxic system that makes those lucky few excessively rich or powerful.

One increasingly common fast track to notoriety comes through social media attacks on “the establishment.” This phenomenon and accompanying philosophy is evident in the example of 23-year-old Twitter activist Suey Park who garnered national headlines earlier this year with a call to cancel The Colbert Report based on a tweet that offended her. Despite her 23,000 followers at that time, she described her social justice activism in the New Yorker as follows:

“There’s no reason for me to act reasonable, because I won’t be taken seriously anyway,” she said. “So I might as well perform crazy to point out exactly what’s expected from me.”

The implications of this statement are that the system is too powerful to be dealt with rationally, that an audience of 23,000 people is not substantial enough to warrant personal accountability, and that mirroring the irrationality of the system is preferable to joining it with an intention to make it better. Park is not alone in her reasoning. Online discourse is full of marginalized citizens expressing anger and helplessness in the face of perceived injustices. It’s not a stretch to expect this notion of personal power will lead to a future society replete with irrational actors.

To balance this bleak picture, the example of NSA leaker Edward Snowden comes to mind. Snowden worked within the system and took it upon himself to countermand the National Security Agency’s entire playbook. He maintains that trying to change the intelligence-gathering machine via proper channels would have failed. An examination of the fallout from Snowden’s intel-bomb proves him right. While the media responded with a full-throated cry to label Snowden a “hero” or a “traitor,” the real questions are dead in the water. Who among us is glad to know what our elected officials have been up to and what, if anything, needs to change now? Are we still okay with the Patriot Act, a set of legal procedures that we knowingly permitted our elected officials to enact more than a decade ago? Does a system of covert government controls that once alleviated our fear in the aftermath of 9/11 still serve us? (Based on the current state of this discussion, I’d wager that another terrorist attack will answer these questions for us before we, as citizens, take substantive action to resolve them.) There is no resolution to this story yet. Snowden might be a hero or a traitor, or both. What is clear is his sacrifice of personal freedom for a political principle, and this makes his choice compelling where online ranting is not.

Running counter to these rogue actors and the “i” generation are Donald Rumsfeld and his contemporaries. Serving was the ideal most uttered by Rumsfeld’s generation, specifically serving one’s country, not serving oneself. Upholding the system and “doing their part” was a common refrain in mid-20th century speeches, even as the baby boomers protested the Vietnam War. Ask not what your country can do for you… Today, “service” and “sacrifice” aren’t words you hear many 20-somethings use, vernacularly, and the reasons for that may be rooted in America’s shifted values. Our culture celebrates the notion of making millions of dollars, ostensibly to avoid sacrifice and service of any kind.

Thousands of engineers, designers, marketers, lawyers, and inventors do, in fact, serve in the shadow of “cool” and “awesome” visionaries like Elon Musk, while our government bureaucracy, military outfits and private sector corporations are lazily referred to as necessary evils without a charismatic figurehead to sell the public on their personified goodness.

How people perceive their service is being perceived has become an integral part of individual identity.

Thus, feeling good about a decision is now as-or-more important than the decision itself. What any leader will tell you is that you often can’t feel good about your decisions because they’re rarely black-and-white options you’re choosing from. You’re paid to make complex decisions that almost always sacrifice one desired outcome for another. Holding out for the perfect, feel-good option results in paralysis. No one feels good about dropping bombs unless they’re blind to the risks. Nothing in The Unknown Known indicates Rumsfeld was blind.

To that end, Rumsfeld was the ideal figurehead for America’s military in 2001, the perfect pitch person to take the country to war — a guy with decades of experience who loved to spar with the press, whose obvious enjoyment of life, and power, emboldened a bewildered, bereft public to strike back after they’d been hit. Make no mistake, we all had a desire to hit back. It is disingenuous to deny having those feelings in the aftermath of 9/11, and yet in our black-and-white discourse we pigeonhole ourselves into “pacifist” and “warmonger” camps, effectively taking the complexity of crafting an appropriate response to the 9/11 attacks off the table. Rumsfeld was in the Pentagon when an airplane flew into the building, as close as any person could be to the physical attack. He describes the pieces of the airplane strewn across the grass, and footage shows him carrying his injured personnel away from the building. I wondered why Morris didn’t ask Rumsfeld about his personal feelings toward the enemy or whether he desired revenge. Morris clearly agrees with Shakespeare: history is teeming with flawed people in power, driven by emotion, acting on impulse and motivated by greed, so why not invite Rumsfeld to reflect in a personal capacity? Is it because this will make him more relatable? More human?

What becomes evident from The Unknown Known is the disconnect between Rumsfeld’s understanding of his role in a new millennium, the exponential increase of personal power over the last several decades that made him singularly responsible in the public’s eyes for guiding the country toward military action in the Middle East. His willingness to talk to the press during the Bush Administration was clearly a function of his enjoyment of interaction, but he did not fully grasp the character of his audience, the general public, nor his soldiers, some of whom perpetrated horrific abuses on our prisoners of war and proudly catalogued photographic evidence of said abuse to share with friends. For all of his time spent imagining potentially terrible outcomes, Rumsfeld’s understanding of personal power did not stretch to include rogue actors in his own army. Equally blind, these rogue actors had no understanding of how their actions weakened the United States and, in Rumsfeld’s view, gave power to the terrorists.

Rumsfeld: “I testified before the House, testified before the Senate, tried to figure out how everything happened. When a ship runs aground, the captain is generally relieved.”

[cut]

Rumsfeld: You don’t relieve your presence? [sic; does he mean presidents?]

[cut]

Rumsfeld: And I couldn’t find anyone that I thought it would be fair and responsible to pin the tail on, so I sat down and wrote a second letter of resignation. I still believe to this day that I was correct and it would have been better, better for the administration, and the Department of Defense, and better for me, if the Department could have started fresh with someone in the leadership position.”

Morris: “So you wish it had been accepted.”

Rumsfeld: “Yes.”

The Abu Ghraib scandal occurred in 2003. Bush kept Rumsfeld on as Secretary of Defense until 2006. What the American public should then ask is: Why wasn’t his resignation accepted? In light of everything that went wrong with our military action after 9/11, why would Bush keep him on?

CONCLUSION

Even as Rumsfeld gamely debates Morris, compliantly reads his own memos aloud and lays out events with candor, he is portrayed unequivocally as “the bad guy.” Yet, for all of my personal horror at the decisions that were made during Bush’s administration and Rumsfeld’s tenure at DoD, I came away from the film with a clear sense that Rumsfeld was a rational actor who understood the scope and limits of his role and, in fact, did his best to uphold the values of the system. Many Americans did, and do, agree with his actions. While many of us see the system as corrupt, and the Bush Administration as manipulative, it is notable that Bush was reelected in 2004. It wasn’t until the country finally registered a change of heart over the war in the 2006 midterm elections and shifted power to the Democrats that Bush was forced to make a change; Rumsfeld was out.

It turns out Rumsfeld’s untold crime might be that he sticks to what he knows. He doesn’t read legal briefs – “I’m not a lawyer.” – and he’s not a detective or a policeman. He recounts the day he took over the Chief of Staff office in the Ford Administration and discovered a locked safe in one of the cupboards. It had belonged to Nixon’s Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman, and remained unopened in the office through Alexander Haig’s short tenure. Rumsfeld asked his then-assistant Dick Cheney to dispense with it through a proper chain of evidence without opening it. Investigating crimes and bringing people to justice were not his areas of expertise. In another era, this blinders-on approach to work was respected. Today, anyone with access to the internet and a search engine is a for-a-day doctor, lawyer, psychologist or war strategist, and Rumsfeld’s dispatching of the safe signals a refusal to get his hands dirty. However, Rumsfeld is of an earlier generation. He followed protocol and got on with his job.

The unspoken aspects of Rumsfeld’s interview are surprisingly easy to miss. There is so much information and history presented, and so much energy in the back and forth between subject and interviewer, that it only came to me later how terribly sad it must be for someone as ambitious as Rumsfeld to end his career the way he did. The personal failure he expresses in the film is dwarfed by the magnitude of torture memos, detainee abuses, and evidence of his ineffectiveness in controlling the military. That Rumsfeld doesn’t mention this sadness, or elicit sympathy for his personal losses, is characteristic of the stoicism of his generation. It’s easy to loathe someone who represents failure, manipulation, abuse of power, and death, but I had a strong feeling after watching this film that he was being dehumanized as penance for our mistakes as well as for his. It troubled me that Morris didn’t pave the way for Rumsfeld to be human on camera. Someone has to go first. Because I inherently relate to Morris’s anger over the war, I hold him to a higher moral standard. He represents me in this film, and I wanted him to offer detente.

Morris’s final question to Rumsfeld is “Why are you doing this? Why are you talking to me?” Rumsfeld responds that it’s a vicious question, and in light of his compliance with Morris’s format, it is exactly that: a vicious question. Whether you agree or disagree with Rumsfeld’s decisions, he’s a public figure with political aspirations who left a paper trail millions of miles long and willingly explains their content. He admits to fretting over complex choices that had to be made but didn’t permit self-doubt to paralyze him. The opposite complaint is lodged against the current administration. There is no winning this either/or war. Careful consideration is a habit we hope for in our leaders because it’s the appropriate way to deal with complexity. Morris ends up looking like he would prefer Rumsfeld were more dogmatic than thoughtful. It’s a trap of the quagmire Morris waded into. The quagmire of quagmires.

What Rumsfeld likely knows, and the American public can’t stomach, is that he did the job he was appointed to do and therefore any apology would ring hollow. Americans elected the wrong president to lead them in the aftermath of a brutal attack. George W. Bush only needed the public’s grief to justify a war, nothing else. Morris supplies evidence, unsolicited, to support the notion that Rumsfeld wouldn’t necessarily have taken us to full-blown war of his own volition: the Swamp memo from all of those years ago. This is potentially as transparent as politics gets. The American public sought revenge after 9/11. Rumsfeld served us.

It’s difficult to say “Rumsfeld isn’t evil” when you look at the photographs from Abu Ghraib. Taking away the “evil” moniker will make some feel like the abuse and deaths he caused, through orders, through policy, and through mistakes, are less honoured or properly remembered. Personally, I think the opposite is true. Mischaracterizing a leader so that we feel better about blaming him is exactly the mistake we made to get us into the Iraq war in the first place. We expanded upon Hussein’s “evilness” to justify our actions. By making that mistake again in analyzing our own leaders, we’re dishonouring the scarred and the dead.

Either Americans were deceived by members of the Bush Administration (which I think is true), or the government was relying on intelligence that turned out to be false (as Rumsfeld, Colin Powell, and others have averred, which I also think is true.) However, Americans’ willful self-deception is the greatest crime of all. That Rumsfeld refuses the role of bad guy or hero in his narrative is what seems to confound Americans most. They want an apologetic villain or a delusional king but they have no apparent capacity to see Rumsfeld for what he is: a decision-maker whose rise to power meant that his failures were amplified and spectacular. This is not absolution, it is a statement of events. The question we should ask ourselves now is: Can Donald Rumsfeld and Errol Morris share a national identity? The answer has far-reaching implications for the future of the country.

The country is in the crosswalk arguing passionately over the correct place to stand, in the black or in the white. Sidewalks are gray, and frankly that’s where we should be doing our arguing if we want to avoid another tragedy. Americans would best use their time, then, by moving past the desire to elicit apologies from their would-be villains. Placing blame and bestowing forgiveness won’t ameliorate the gnawing guilt over so many fallen and wounded soldiers and civilians. Instead, people should take a hard look at where they might participate in remedying or, better yet, rebuilding a broken system. To do that effectively, people with conflicting views will have to listen to each other. Morris and Rumsfeld begin that process in The Unknown Known by sitting down to talk.