A Review of Rebirth, Dir. Jim Whitaker

Rebirth opens on a black screen with audio of a jocular morning deejay talking about the weather in New York City on September 11th, 2001. There is a perceptibly light quality to the deejay’s voice, a casual, unforced ease that has yet to fully return to American society, and hearing it is akin to hearing a younger self talk on tape. It’s amazing we were ever that innocent.

Rebirth is the documentary film directed by Jim Whitaker that chronicles ten years in the lives of five people directly affected by 9/11. He interviews them once a year, every year, beginning in 2002. Concurrently, Whitaker and Director of Photography Tom Lappin set up time-lapse cameras around Ground Zero in 2002. The cameras are still in place today, effectively capturing the aftermath of destruction, the methodical clearing away of debris, and the rebuilding of the site.

Rebirth is a movie about resilience.

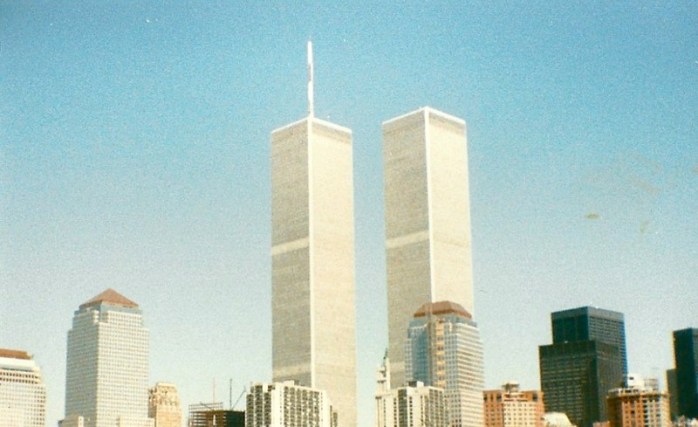

For a director sitting on ten years worth of footage, it’s an impressive choice to use as much black screen throughout the film as Whitaker does. We don’t see the planes fly into the World Trade Towers. We don’t linger on shots of awestruck New Yorkers staring at the sky. We don’t watch smoke billowing, and we don’t wait in torment for the moment those towers crumble and fall. Instead, Whitaker wisely gives us audio clips of real time reactions from news anchors and people on the street over a black screen, leaving visual space to recall our own images of that day and adjust to the truth a little bit more. We can’t learn anything further from a new clip, an angle we haven’t seen, or a detail we missed. This happened, it can’t be undone, and time marches forward regardless of how we feel about it. The black screen permits us to recall that day in the same way we recall any trauma: by memory. Whitaker demonstrates profound understanding of grief in his choices.

When we first meet the five subjects in 2002 they are all still in shock. They recollect the events of 9/11 with varying degrees of numbness and hysteria. They articulate denial and disbelief. They search the floor for words. They hold the interviewer’s gaze, needing a sign that their pain and confusion are mirrored, and knowing that they can’t be. Each of their losses is deeply personal. Mike Lyons is a construction foreman down at Ground Zero. He lost his brother, a fireman, on 9/11; Tim Brown is a fireman who lost all of his friends that day, including his best friend, and his mentor. Nick Chirls is a teenager whose mother had recently started a new job on Wall Street and never came home. Tanya Villanueva Tepper’s fiancé was a fireman who never came back. Ling Young was in the South Tower when the second plane hit and she suffered severe burns across her body. She lost her life as she knew it.

We meet these people already changed and struggling to process their immeasurable losses. Their lives are in pieces. The miracle of this film is watching them reconnect to parts of themselves that are capable of happiness and peace, parts they believe beyond a doubt to be dead and we, as strangers, never expect to meet. We’re told by each of the subjects at the outset that they don’t know how to move forward, that what they’ve lost can never be replaced, and we know they’re right. At the same time, we have ten years’ distance and a readiness to believe that time will bring more understanding. The observations each person makes, about their tragedy, about life, about love, about the nature of loss and pain, are poignant, all the more so for their willingness to reveal such personal grief on film. One hopes it’s another form of healing; the sacred sharing of memories. One of the most astounding recollections is given by Nick, who tells of the moment he stepped up to the podium to memorialize his mother and a sparrow flew into the building and landed on his head. The home movie footage is riveting; we wouldn’t believe it if we couldn’t see it. He reaches up and the bird allows him to hold it. He passes it to someone else, and the bird flies away. It’s a moment that defines him in the coming decade as we watch him mature from boy to man, his attachment to his mother somehow calling her forth from beyond.

Parallels between emotional pain and physical pain abound in our culture (note the widespread use of the term “broken heart”), but the two kinds of pain are substantially different. The juxtaposition of Ling Young’s decade of surgeries, skin grafts, peels and joint replacement to the emotional anguish of the four survivors who grieve for their loved ones is a testament to the complexity of pain. In some ways, Young’s story is most difficult to watch because of the extreme nature of her injuries; her healing seems unlikely and the hopelessness is unbearable. It’s difficult not to become numb with her.

Everyone has a relationship to death and can find a way to relate to emotional pain, if they choose, but many of us never experience the physical trauma of third degree burns. Meeting Young in 2002, there is little clue as to what kind of person she is, of her temperament, beyond what she tells us in a lifeless tone. The other subjects express their former selves through declarations of love and loss, but Young’s numbness precludes access to her former self for the viewer. The first five or six years only strengthen the notion that this woman is a pessimist, probably always was a pessimist, and that the rest of her life will be filled with unhappy thoughts and severe physical limitations. Then in one year, roughly 2008, everything changes. Suddenly, Young turns up to the interview as an entirely different person and we meet the woman who had a life before 9/11. She mentions attending a burn victims conference, and in describing the experience, the audience is privy to the woman under the burns, a happy, optimistic, energetic woman capable of great joy and sharp wit; she has broken through the numbness. She will never be rid of the scars. She will never have full use of her hands. Yet, she transforms internally, as do the other survivors, and the relief in watching her smile is overwhelming. In fact, the subjects all turn a corner in their lives within a year or two of each other. One achievement of this film is its demonstration that we heal emotionally from all kinds of pain in roughly the same amount of time, and we shouldn’t push people to “get over” something, or avoid people in pain because we’re afraid of the numbness we feel around them. We can and should hold fast to a sense of optimism for recovery for everyone, always, no matter how long it takes.

I watched September 11th unfold while kneeling in front of my sister’s television in Los Angeles. When the first tower fell, I leapt forward and my hand flew to the screen, my palm pressed to the caving building. I don’t know if I wanted to catch the tower or touch the people in it, but it was an instinctual response that defied logic. Each of the people in Rebirth bravely recount their experiences and feelings, no matter how raw, or illogical, with an openness that is inspiring. They insist they aren’t brave, but their strength of spirit is palpable. By embracing that which they’re most afraid of—of betraying the memory of a loved one, of never being able to love again, of disappointing a parent, of giving up on life—each person comes full circle to themselves and happiness finds its way back in new, unexpected forms. It is also an act of courage to make this documentary, knowing that even the best of intentions might cause suffering. In allowing viewers their own grief over 9/11, without retraumatizing them with images, Whitaker gently paves the way to focus on his subjects’ grief. The experience of this film is unique in its demonstration of healing; the viewer is permitted, encouraged, even dared, to heal as well. The film gives a voice to people’s grief, and in doing so lovingly, it heals.

Rebirth is currently available on Netflix, Amazon, Apple, and other streaming services.